“I’m so grateful that his blood runs in our veins,” mentioned Tewanna Anderson-Edwards of her nice uncle Otis W. Chief, a World Battle I Choctaw code talker.

Chief, a corporal within the Military’s sixteenth Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, as soon as destroyed a machine gun nest singlehandedly after a few of his males had been killed, capturing two machine weapons and defeating 18 enemy troopers within the course of.

He would go on to obtain the Purple Coronary heart, the Silver Star Medal, the Victory Medal and French Croix de Guerre with Palm, amongst different awards.

Normal John J. Pershing even as soon as referred to Chief as one of many “struggle’s best preventing machines,” in accordance with the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

However regardless of these accolades, Chief and different WWI code talkers — service members who used Indigenous languages to create undecipherable communications — nonetheless haven’t obtained the popularity they deserve, Edwards believes.

“There’s simply no telling what number of lives they saved,” Edwards advised Army Instances.

A transfer to rectify that, nevertheless, could also be on the horizon.

Chief is one in all a bunch of Indigenous veterans who’re at present being reviewed as potential recipients of the Medal of Honor — greater than a century after they served. In all, roughly 12,000 Native Individuals served throughout World Battle I.

“It’s my final objective to see that he will get his due recognition. … He so deserved it,” Edwards mentioned. “He wasn’t only a code talker, he was a struggle hero.”

Chief’s eligibility for the Medal of Honor comes as a part of the World Battle I Valor Medals Overview Act, which was handed as a part of the 2018 Nationwide Protection Authorization Act.

The legislation permits for a overview of actions by non-white veterans who served in World Battle I to find out whether or not choose acts of valor, which had been throughout that interval usually diminished on account of one’s pores and skin shade, warrant the nation’s highest navy honor.

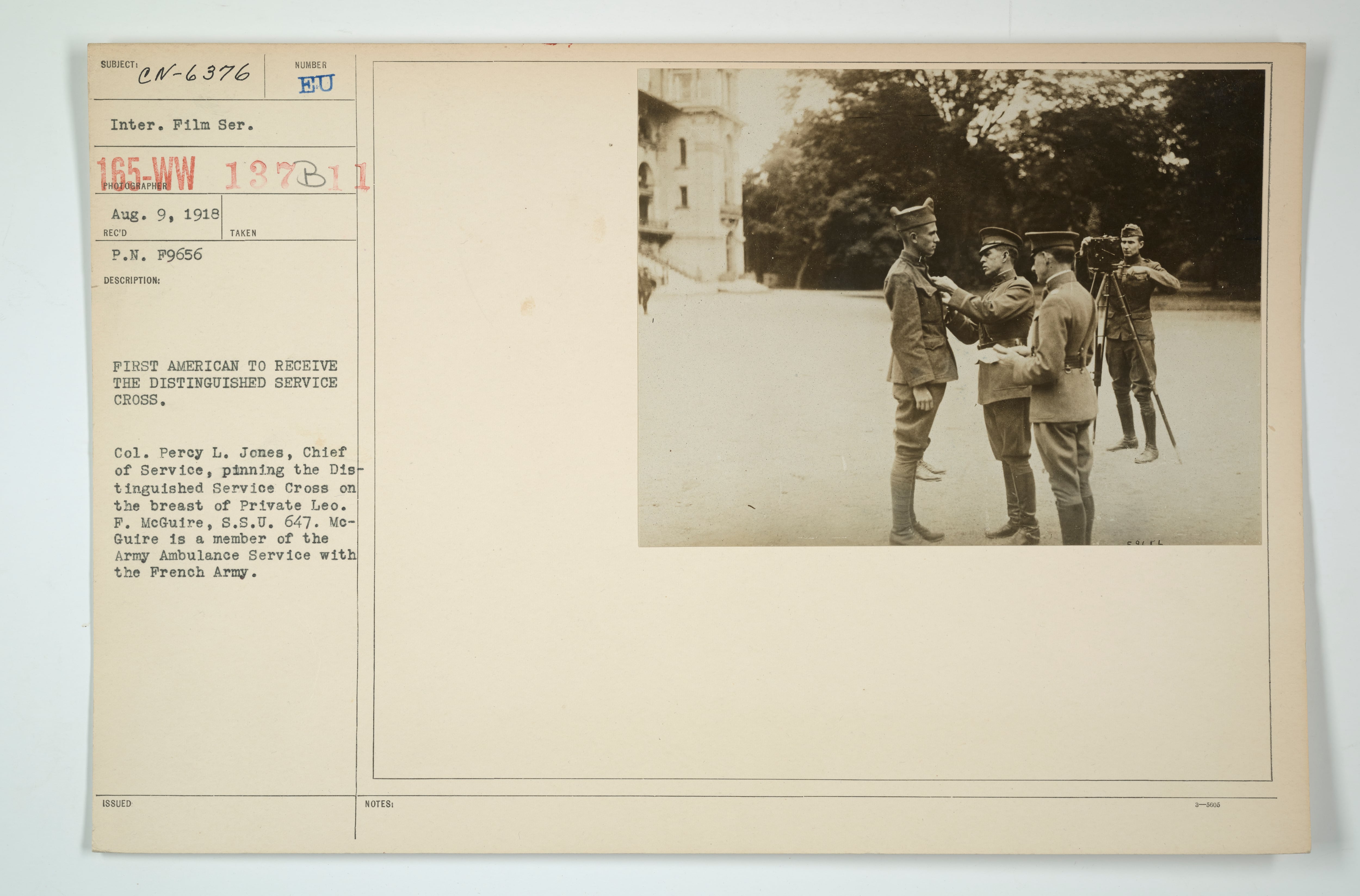

To qualify, veterans from numerous racial backgrounds should have been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, French Croix de Guerre with Palm or have been really helpful for a Medal of Honor.

As soon as such a service report is delivered to the eye of the Military or Navy, the related department evaluations the report and points a willpower concerning award standing.

As a part of that course of, the Pentagon was suggested to collaborate with the Valor Medals Overview Job Drive, a joint operation run by the World Battle I Centennial Fee and Park College’s George S. Robb Centre for the Examine of the Nice Battle.

Dr. Timothy Westcott, the Missouri-based division’s director, advised Army Instances he first got interested within the topic after he noticed a college presentation throughout Black Historical past Month about Sgt. William A. Butler, a Black struggle hero who was nominated for, however by no means obtained, the Medal of Honor.

In September 1918, George S. Robb — the division’s namesake — was really helpful for a Medal of Honor on the identical piece of paper as Butler. Whereas Robb would go on to obtain the nation’s highest navy ornament, Butler could be introduced a Distinguished Service Cross.

From there, Westcott acquired concerned with the Centennial Fee, which oversaw the Valor Medals Overview Undertaking and Job Drive and researched veteran service information to make retroactive award suggestions to the Pentagon and Congress.

When the fee disbanded in 2024 after finishing the Nationwide World Battle I Memorial in Washington, the Robb Centre took cost of that effort.

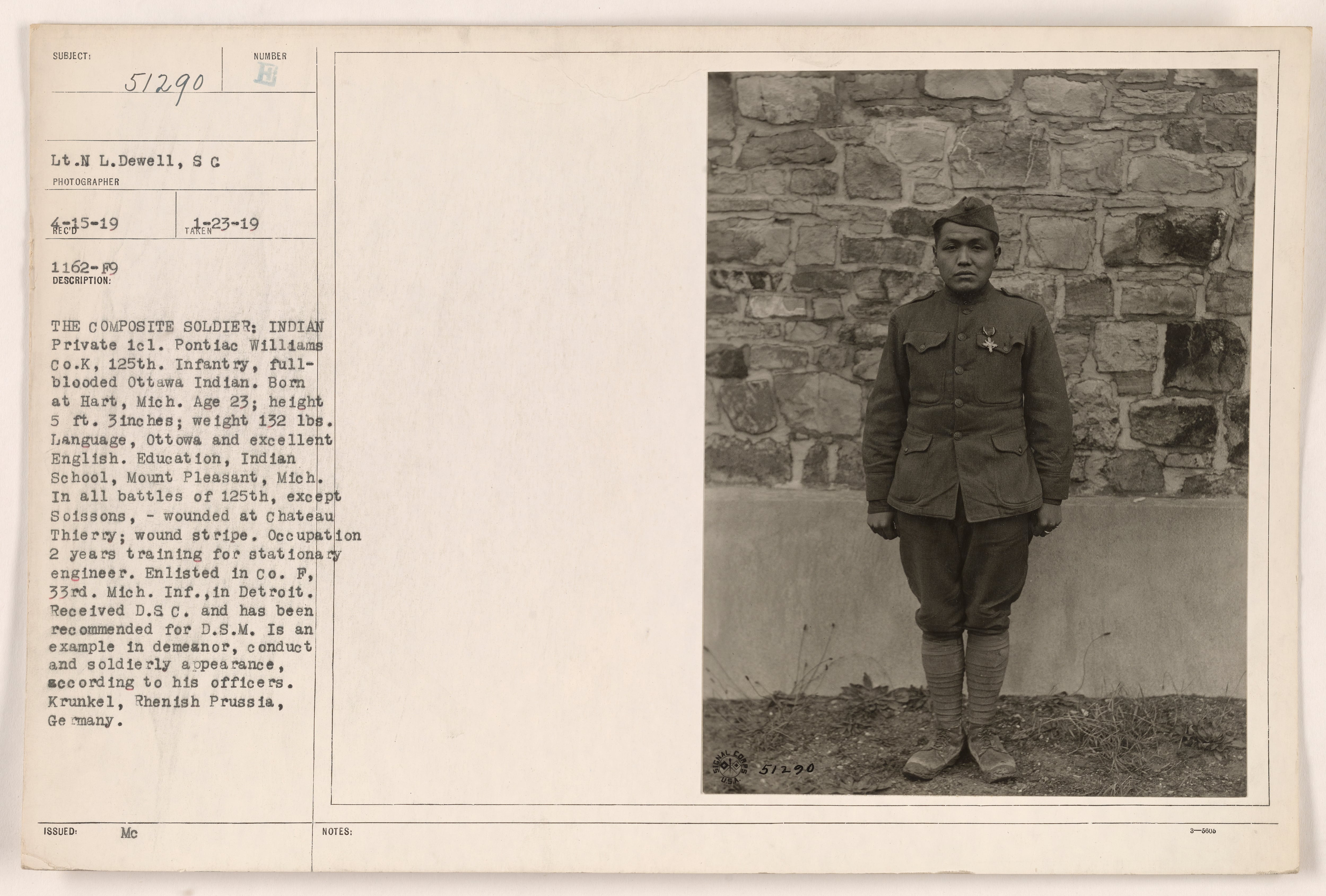

Thus far, Westcott and the division have recognized 214 service members from World Battle I who met the factors for Medal of Honor eligibility. Of these, 24 are Indigenous veterans.

“We’ve got submitted 56 [total] nomination packets,” he mentioned, noting that the method is especially grueling. “It takes us about six to 9 months to put in writing a nomination packet, and people are roughly 150 to 165 pages in size every.”

Of the 56 packets Westcott’s group has submitted, 49 have been despatched to the Military. The opposite seven have gone to the Navy.

There’s at present no timeline for approval. As soon as Westcott and his group submit the packet, there’s restricted contact between the middle and the service, he mentioned. Because the division submitted its first packet in 2022, the Military has supplied only one follow-up communication.

Earlier than it disbanded, the Centennial Fee labored with the Sequoyah Nationwide Analysis Middle on the College of Arkansas at Little Rock to construct a database of all Indigenous personnel who served in World Battle I.

Erin Fehr, the assistant director and archivist for Sequoyah who helped assemble the database, advised Army Instances that the thought for it got here after she put up a 2017 exhibit on the WWI code talkers.

“Most individuals affiliate code talkers with World Battle II, when in actuality they started within the first World Battle,” she mentioned.

However as Fehr was getting the exhibit collectively, an absence of public consciousness of Indigenous navy service throughout the First World Battle turned obvious.

“[Visitors] didn’t even understand that Native individuals had been concerned within the struggle in any respect,” mentioned Fehr, who’s Yup’ik.

So, Fehr launched into a journey to seek out as many names of Native American service members from World Battle I as potential to determine a wall of honor, itemizing veterans by tribal affiliation. In three months, she and the middle had found 2,300 names that they taped to a wall within the exhibit for guests to see.

However there was rather more work to do.

“We haven’t discovered these 12,000 names,” she mentioned.

Since then, Fehr and Sequoyah have been relentless in compiling a complete record, with the group at present monitoring round 6,200 names.

Westcott approached Fehr a while in late 2018 or early 2019, Fehr mentioned, and requested for the middle’s help to find Indigenous service members who could also be eligible for the Medal of Honor beneath the World Battle I Valor Medals Overview Act.

Fehr jumped on the alternative to collaborate.

“The entire goal behind this mission was to not preserve the knowledge for ourselves,” she mentioned.

Fehr mentioned portion of her analysis and findings have come from periodicals launched by the American Indian boarding college system, since many service members had been despatched to such locations throughout their youth.

American Indian boarding faculties had been erected within the late nineteenth century and devised as a approach to eradicate the traditions and languages of Indigenous peoples — oftentimes by means of verbal, bodily and sexual abuse — whereas forcing assimilation. There have been greater than 523 such faculties working at one time, in accordance with The Nationwide Native American Boarding Faculty Therapeutic Coalition.

“Kill the Indian in him, and save the person,” mentioned R.H. Pratt, the founder and superintendent of Carlisle Indian Industrial Faculty, the primary federally run Indigenous boarding college.

A current Washington Submit investigation discovered that greater than 3,100 college students died at American Indian boarding faculties, greater than thrice the quantity the U.S. authorities beforehand reported.

Fehr identified the grim paradox at play for Native Individuals who attended boarding faculties after which joined the ranks: All their lives, they’d been chastised for talking their language. In lots of circumstances, it was crushed out of them. However after they enlisted to serve the nation that had wronged them, it was their language they had been advised was key to defeating the enemy.

Fehr additionally defined that the navy was uncertain learn how to deal with Native American enlistees main as much as World Battle I due to boarding faculties. Contemplating the objective of the faculties was to realize assimilation into white tradition, holding Indigenous troops separate would sign that the federally funded faculties had failed.

The U.S. finally determined to combine the ranks.

Amongst these males was Chief, of whom Edwards says she now has solely obscure reminiscences — specifically, his palpable heat and exquisite smile.

“He was like an enormous Santa Claus to me,” she mentioned.

Due to Chief’s demeanor, nobody would ever guess the tragedies and adversity he confronted within the struggle, she added.

However his story is one Edwards hopes will quickly be acknowledged with the best navy honor. And it’s one in all many within the Indigenous group she hopes can be extensively shared.

“We’re simply now starting to discover a stability,” she mentioned, “between by no means forgetting and shifting ahead with all this.”

Riley Ceder is a reporter at Army Instances, the place he covers breaking information, felony justice, investigations, and cyber. He beforehand labored as an investigative practicum pupil at The Washington Submit, the place he contributed to the Abused by the Badge investigation.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/4GX3EMIJJNC3DMQKVRDLGXGROQ.jpg?w=120&resize=120,86&ssl=1)