First Lt. Kermit A. Tyler was the following man up on the squadron obligation roster, so he resigned himself to spending the approaching Sunday morning, 4 to eight a.m., on the Plane Info Middle at Fort Shafter on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. At 3 a.m. on that day, Dec. 7, 1941, the 28-year-old fighter pilot drove south from his home on Oahu’s North Shore to Fort Shafter, listening to Hawaiian music on his automotive radio.

The Info Middle was the hub of a cutting-edge system designed to warn of air assaults aimed toward Hawaii. A half-dozen radar stations have been situated all through Oahu, the location of a number of navy bases together with the naval base at Pearl Harbor. The radar operators’ job was to detect approaching planes and report uncommon contacts to the middle. Middle personnel would consider the knowledge and decide if the plane may be hostile, during which case they’d scramble pursuit planes to intercept them.

The concept was sound, however the system was not but a smooth-running operation. Pilots have been randomly despatched to man the middle, serving as little greater than heat our bodies. Tyler, for instance, had no coaching in radar — and no concept what he was purported to do on the middle. A number of days earlier, he had requested his superior, Main Kenneth P. Bergquist, about his position. Bergquist solely prompt that if a aircraft crashed, Tyler might assist with the rescue operation. Even the middle’s location was makeshift: a room above a warehouse, pending development of a everlasting dwelling.

The primary three hours of Tyler’s Sunday shift have been uneventful, even boring. Solely a skeleton employees was on obligation. The officer whose job it was to establish approaching plane wasn’t scheduled to be there that morning, but it surely didn’t appear to matter as a result of there have been few planes within the air. Tyler handed the time writing letters dwelling and thumbing by way of a Reader’s Digest. However at 7:20 a.m., destiny intervened to make sure the younger pilot an unwelcome and enduring place in historical past, branded as the person who had an opportunity to thwart the Pearl Harbor assault — however didn’t.

Born in Iowa in 1913, Tyler grew up in Lengthy Seaside, California. After two years of faculty, he joined the Military Air Corps in 1936 and earned his wings the following 12 months. In February 1941, Tyler was assigned to the 78th Pursuit Squadron in Hawaii. For a younger airman, life in idyllic Oahu was “very nice certainly,” he mentioned. He and future ace Charles H. MacDonald shared a seaside home on the North Shore, splitting the $60 month-to-month hire, and Tyler took up browsing, an avocation he pursued for the following 50 years.

Whereas Tyler and his fellow pilots honed their flying expertise with aerobatics and mock dogfights of their P-40 Warhawks, different officers studied technological advances that will assist win the following struggle. One of the vital promising was often known as “radio detection and ranging,” or radar. When high-frequency radio waves hit an object, like an airplane, they deflect again, producing a picture on an oscilloscope display pinpointing the item’s location. The British had pioneered necessary advances within the subject; the earlier 12 months, radar had proved pivotal within the Battle of Britain, alerting the Royal Air Power to approaching German bombers and enabling its fighter planes to intercept them.

The arrival of plane carriers had made even island outposts like Hawaii susceptible, so radar turned the linchpin of Hawaiian air protection. Working on the higher finish of the present-day FM broadcast band, the radar units in use on the time, referred to as SCR-270Bs, might detect planes greater than 100 miles away. Nonetheless, they’d limitations. Foremost, they may not distinguish between pleasant and enemy planes. The British had expertise to do this — a system referred to as Identification, Buddy or Foe — however the U.S. Military Sign Corps was nonetheless creating an American model. The SCR-270B additionally couldn’t discern the variety of planes in a contact.

Many junior officers had embraced radar, however the higher-ups confirmed little curiosity, famous Main Bergquist, who was establishing the Hawaiian radar system. Cmdr. William E. G. Taylor, a navy officer then engaged on radar in Hawaii, noticed that radar was “type of a foster youngster at the moment, we felt.” Turf battles between the Sign Corps and the Air Corps didn’t assist both, Bergquist mentioned; the consequence was bureaucratic inertia, a scarcity of educated personnel, and a scarcity of spare components, which restricted radar station working hours to 4 to 7 a.m. every day. Even after they have been lively, the units weren’t used to detect hostile plane. As an alternative, radar was used extra to coach for hypothetical future threats quite than for “any concept it might be actual,” defined Lieutenant Normal Walter C. Quick, the military commander in Hawaii.

By late 1941, American relations with Japan had reached their breaking level. U.S. Military Chief of Workers Gen. George C. Marshall issued a struggle warning to Normal Quick on Nov. 27, alerting him to “hostile motion potential at any second.” Marshall additionally ordered Quick “not, repeat not, to alarm the civil inhabitants,” so Quick confined Marshall’s warning to officers he deemed to have a have to know. Quick positioned his command on alert — however on the lowest potential alert stage, one which warned solely in opposition to “acts of sabotage and uprisings inside the islands, with no risk from with out.”

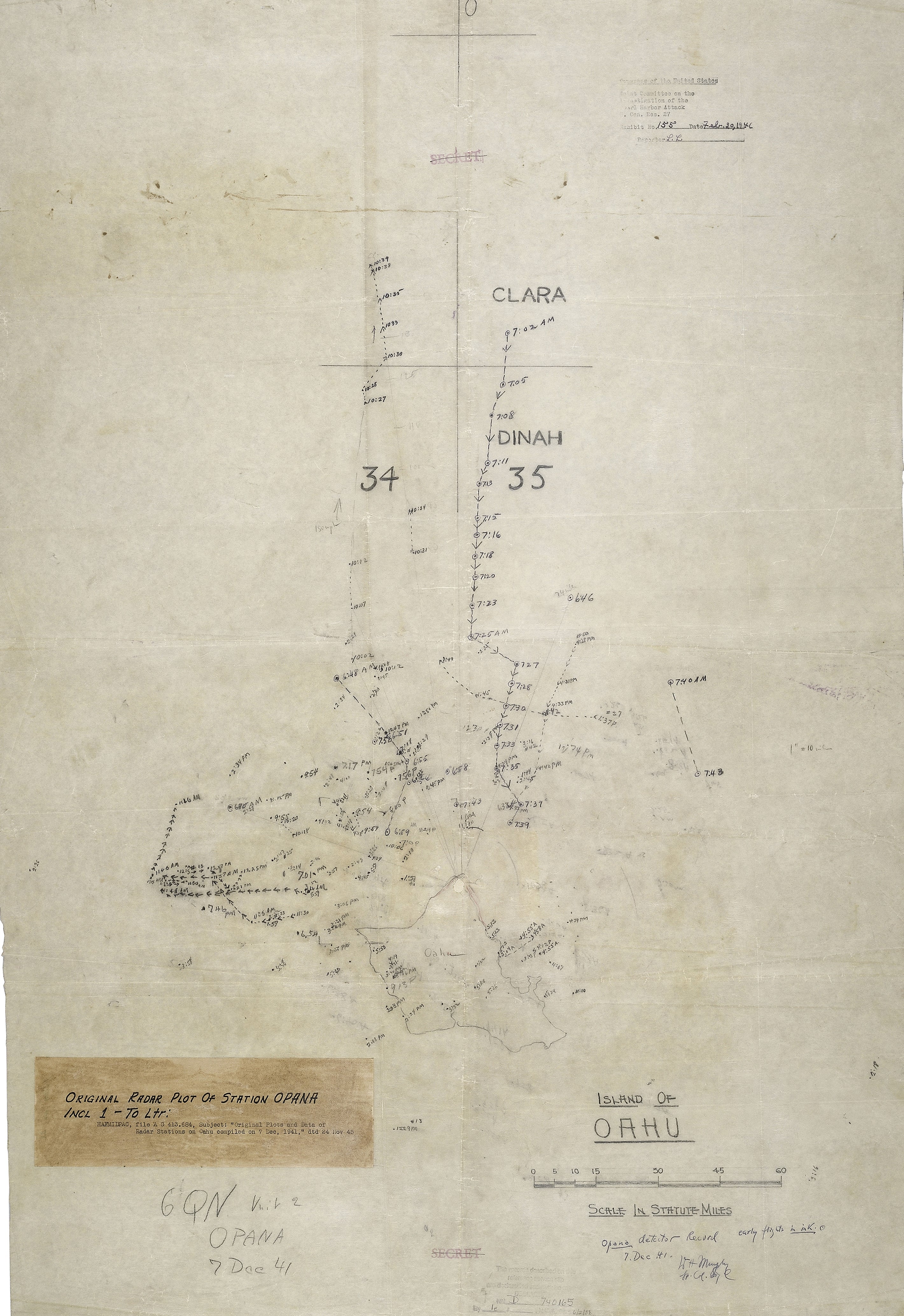

On the similar time that Tyler began his shift on Dec. 7, Non-public Joseph L. Lockard, 19, and Non-public George E. Elliott Jr., 23, fired up the radar station on Opana, some 30 miles north of Fort Shafter, on the higher tip of Oahu. Of the 2, Lockard was the extra skilled, though he had no formal education in radar. He operated the SCR-270B, and Elliott plotted radar contacts on a map. It was a “quite boring morning. There was not a lot exercise,” Lockard recalled. At 7 a.m., with the day’s scheduled radar operations accomplished and an hour remaining in Tyler’s shift, Lockard and Elliott ready to close down. However the truck scheduled to carry them again to their camp was late to reach; within the meantime, they saved the radar on to offer Elliott apply working it.

At about 7:20 a.m., Elliott reached the middle’s switchboard operator, Non-public Joseph P. McDonald, and gave his report: “Giant variety of planes coming in from the north.” McDonald thought that he was alone and didn’t know what to do. When he noticed that Tyler was nonetheless on obligation, he had Tyler converse with Lockard. Lockard instructed Tyler concerning the contact, which was now 20-25 miles nearer to Oahu, deeming it essentially the most substantial studying he had ever gotten.

Tyler remembered the Hawaiian music he had heard on his automotive radio earlier that morning. He knew that the radio station, KGMB, broadcast in a single day solely when American heavy bombers flew in from the mainland. The Air Power wished the station’s sign accessible as a navigation assist. That have to be it, Tyler thought, and he concluded that the radar contact was a flight of pleasant planes. He instructed Lockard to not fear about it and determined in opposition to disturbing his superior, Bergquist, who was at dwelling. Within the peacetime navy, Tyler knew, lieutenants didn’t drag majors away from bed on a Sunday morning with out good cause. That this contact may be Japanese planes was the farthest factor from Tyler’s thoughts as a result of he, too, was unaware of Marshall’s struggle warning. In reality, from the information accounts he had learn, he thought the USA’ relations with Japan had truly improved over the previous couple of weeks. Lockard and Elliott continued to trace the planes till 7:39 a.m., after they misplaced them 22 miles from Oahu as soon as the island’s topography interfered with the radar beam.

At 7:02 a.m., his eyes popped at what he noticed on his display: a big blip 132 miles north of Oahu. Lockard was shocked, too, because it was the biggest contact he had ever seen — so massive he initially thought the radar had malfunctioned. After verifying that his tools was working correctly, he instructed Elliott that it regarded like a big flight of planes. The SCR-270B, nonetheless, couldn’t verify what number of planes have been there or whether or not they have been American. Lockard and Elliott have been curious, however not alarmed. Neither had been aware about Marshall’s struggle warning, and neither suspected that the planes may be Japanese. However, the contact was so uncommon that Elliott thought they need to report it to the Info Middle. Lockard laughed and instructed him he was loopy; after some prodding, he relented, and Elliott made the decision.

A flight of 12 B-17 Flying Fortresses was, in actual fact, coming in from California that morning. However what Opana had picked up wasn’t American bombers, however the first wave of Japanese planes sure for Pearl Harbor. They struck at 7:55 a.m. — 35 minutes after Elliott’s name. Tyler sensed an inkling of hassle at 8 a.m. when, his shift over, he stepped out of the middle for recent air. Glancing towards Pearl Harbor, 5 miles away, he noticed antiaircraft hearth and diving planes however thought it was a drill. 5 minutes later, he discovered the reality when close by Wheeler Subject referred to as to report that it was below assault.

The Japanese had achieved full shock. Their assault killed 2,335 American servicemen, sank or broken 19 ships, and broken or destroyed 328 military and navy plane. Since Normal Quick’s alert had warned solely in opposition to sabotage, the planes on the Hawaiian airfields had been lined up wingtip to wingtip — making the planes simpler to protect in opposition to interlopers however straightforward prey for the Japanese attackers.

The Pearl Harbor assault was a seismic shock, and People couldn’t grasp how the military and navy might have been caught so flat-footed. The tragedy turned some of the completely investigated occasions in American historical past, with a presidential fee, an Military board, a Navy court docket of inquiry, and a congressional committee all attempting to determine what had occurred and who was guilty. These panels centered on the commanders — Quick and the Pacific Fleet commander, Adm. Husband E. Kimmel — however Tyler’s dismissal of the Opana radar contact didn’t escape scrutiny.

In 1942, the Roberts Fee, appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and chaired by Supreme Court docket Justice Owen J. Roberts, took testimony and cleared Tyler, noting he had agency cause to imagine that the approaching planes have been American. Tyler’s commander, Brig. Gen. Howard C. Davidson, backed Tyler, telling the fee that Tyler would have wanted “prescience past the odd individual’s capability” to acknowledge the radar contact as Japanese planes.

Two years later, a Navy court docket of inquiry likewise excused Tyler’s failure to heed the Opana contact because of the SCR-270B’s incapability to establish hostile planes and Quick’s failure to disseminate Marshall’s struggle warning. That very same 12 months, nonetheless, the Military Pearl Harbor Board was extra essential, chastising Tyler for failing to name Maj. Bergquist. Tyler “had no information upon which to base any motion,” the board famous, “but he assumed to offer course as an alternative of searching for somebody competent to decide.” The board’s presiding officer was extra understanding. Upon listening to how Tyler had arrived on the middle with out orders or an outlined position, Lt. Gen. George Grunert, a soldier since 1898, famous, “It appears all cock-eyed to me.”

The ultimate investigation, carried out by a congressional committee from 1945-46, positioned the blame squarely on Gen. Quick. Tyler’s failure to alert Bergquist would have been inexcusable had he identified of the struggle warning, the panel concluded, however he didn’t. “The actual cause … that the knowledge developed by the radar was of no avail was the failure of the commanding basic to order an alert commensurate with the warning he had been given by the Struggle Division that hostilities have been potential at any second,” the committee concluded.

For greater than a half-century, historical past fans have debated whether or not Tyler might have modified the course of historical past by passing the Opana radar contact up his chain of command. Would the Military and Navy have been higher ready to fulfill the assault? Navy Secretary Frank Knox thought so. In a report issued on Dec. 14, 1941, he asserted that if the Opana radar contact had been “correctly dealt with, it might have given each Military and Navy ample warning to have been in a state of readiness, which at the very least would have prevented the main a part of the harm performed, and may simply have transformed this profitable air assault right into a Japanese catastrophe.”

Different components, nonetheless, dispel the Navy secretary’s conclusion. Nothing Kermit Tyler might have performed would have been prone to have made a distinction.

The principle obstacle was American complacency — what Chief of Naval Operations Ernest King later referred to as “the unwarranted feeling of immunity from assault that appears to have pervaded all ranks at Pearl Harbor — each Military and Navy.” Japan had been seen as a second-rate energy whose planes and ships have been inferior to their American counterparts. Few imagined that Japan would have the audacity to assault closely defended Pearl Harbor — and it’s onerous to be prepared for an assault believed to be inconceivable. It took defeats at Pearl Harbor, Guam, Wake Island and the Philippines to point out the USA that Japan was certainly a formidable foe.

If Tyler had acted, he would have referred to as Bergquist, who was dwelling in mattress and likewise unaware of Marshall’s struggle warning. For that decision to have had any influence, Bergquist would have needed to have believed the contact may be hostile planes and handed a warning to his superiors. Moreover, Bergquist’s superiors would have needed to have promptly issued a full alert and notified the navy. Given the hubris of which Adm. King had complained, none of those actions was doubtless, as one other incident that December morning exhibits.

At about 6:45 a.m., the destroyer Ward sank a Japanese mini-submarine close to the mouth of Pearl Harbor. The Ward’s skipper reported this motion to his superiors at 6:51 a.m., however naval commanders didn’t take the report severely sufficient to problem an alert. There is no such thing as a cause to imagine that an ambiguous radar contact would have led military commanders to behave any extra decisively than their navy brethren had. Time was additionally quick: Lockard spoke to Tyler at 7:20 a.m., simply 35 minutes earlier than the assault. Even with a immediate alert, there was too little time for ships to get underway or warplanes to get off the bottom.

Probably the most tantalizing “what if” includes an omission that can’t be laid solely at Tyler’s toes. After the assault started, extra skilled officers like Bergquist and Maj. Lorry N. Tindal, an Air Power intelligence officer, took over for Tyler, though Tyler stayed on obligation on the middle. Attributable to “the shock of the assault,” the middle was in “fairly a turmoil,” Tindal mentioned. No Navy liaison officer was current, and nobody from the Military thought to inform the Navy concerning the Opana radar contact till two days later — a lapse that Adm. Kimmel referred to as “incomprehensible.” The Opana station’s radar plot confirmed the trail the Japanese planes had taken to Oahu, a helpful clue to the placement of the carriers that had launched them. If the navy had had that info on Dec. 7, it may need discovered and attacked these carriers, Kimmel believed — however with out it, the Navy chased its tail, looking to the west and southwest as an alternative of to the north.

There was a struggle to be fought, and Tyler moved on. In September 1942, he was promoted to captain and given command of the forty fourth Fighter Squadron, flying fight missions within the Solomon Islands. Tyler was later promoted to main, named operations officer for the thirteenth Fighter Command in Could 1943, and promoted to lieutenant colonel in November of that very same 12 months.

The Opana station’s Non-public Lockard emerged from the Pearl Harbor assault as a minor superstar. On Feb. 10, 1942, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for detecting the Japanese planes. The press portrayed him as one of many few individuals on the ball on Dec. 7, unaware that he had laughed off the radar contact till Non-public Elliott prodded him to report it. Lockard was commissioned a lieutenant and spent the struggle as a radar officer within the Aleutians; Elliott stayed out of the highlight and served as a radar operator within the states for the struggle’s length.

Radar had performed its job in detecting the Japanese planes, and the brass took discover. The assault unlocked a cornucopia of assets for radar operations.

“After the seventh I simply needed to snap my fingers and I acquired what I wished,” Main Bergquist mentioned.

However Pearl Harbor adopted Tyler for the remainder of his life. He remained within the Air Power after the struggle, however a postwar effectiveness report questioned his capacity to react in a disaster — the kiss of dying for development. He retired from the service in 1961 as a lieutenant colonel, the identical rank he had held since 1943. Books and movies have portrayed Tyler as asleep on the swap that fateful morning, and for the remainder of his life, he obtained occasional indignant letters at his dwelling from individuals second-guessing his efficiency at Pearl Harbor. When he died in 2010, newspapers throughout the nation ran his obituary, calling him the person who had ignored the approaching Japanese planes.

Why had destiny singled him out? Tyler had usually questioned. He agonized over whether or not he ought to have performed extra, however in his coronary heart of hearts, he knew the reply: “I might have performed the identical factor 100 occasions, and I might have arrived on the similar conclusion, given the state of alert, or lack of alert, that we have been in,” he mirrored in 1991. Ultimately, Tyler accepted that he was merely the unfortunate man thrust into an inconceivable state of affairs at what had unexpectedly grow to be a pivotal second in historical past, and he made his peace with it.

This story initially appeared on HistoryNet.com.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/ZZJAZCVMVBCTRAZCBQBW6ILR3M.jpg?w=120&resize=120,86&ssl=1)